The recipe

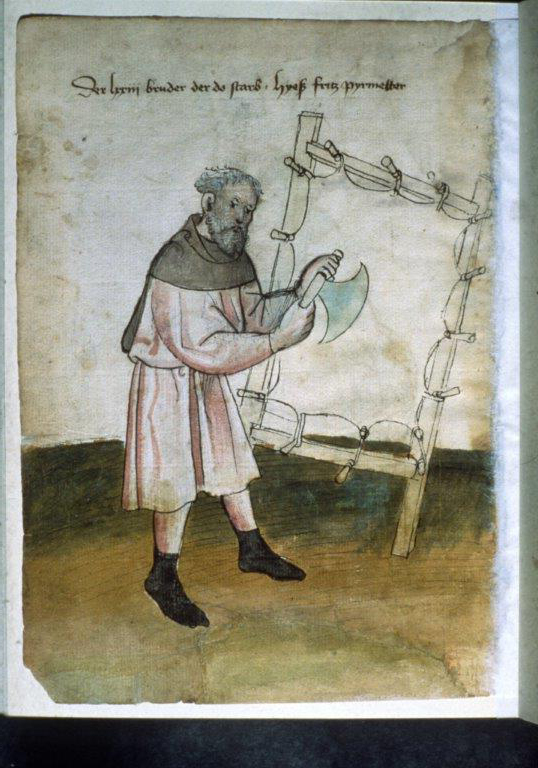

Picture: British Library, Ms Harley 3915, fol.148r.

Ad faciendas cartas de pellibus caprinis more Bononiensi.

Accipe pelles caprinas, et pone in aquam per diem et noctem. Postea

extrahas, et ablue tandiu donec clara inde exeat aqua. Post-

ea accipe uas omnino nouum, et pone intus calcem non recentem et aquam,

et misce bene simul, quod bene spissa sit aqua, et tunc inponantur

pelles, et conplicentur a latere carnis. Postea moueantur cum

baculo singulis diebus bis uel ter, et ita stent in estate

.viij. dies, in hyeme bis tantum. Postea debent extrahi

et depilari. Postea quod in uase est totum debet proici, et aliud eiusdem generis poni in

eadem quantitate, et iterum pelles inponantur et moueantur,

et vertantur singulis diebus sicut primitus per alios .viij. dies.

Tunc debent extrahi et ablui fortissime, quod exeat aqua

clarissima. Tunc debent poni in aquam claram in alio uase

et stare per duos dies. Tunc extrahantur et ponantur corde

et liguntur in circulis, et tunc debent preparari cum bene incidenti

ferro. Postea debent per duos dies absque sole stare. Cum

extracta fuerit aqua, et cum pumice bene fuerit abstracta

caro, post duos dies iterum madefiant spargendo parum

de aqua desuper et purgando bene cum pumice carnem

totam ita madefactam. Postea extendantur corde me-

lius et equaliter, sicut carte debent permanere, et tunc non res-

tat aliud postquam siccate fuerint.

The English translation of the Latin text can be found below in chapter 'The basic technique'.

The basic technique

The early twelfth century recipe that will be followed step by step is one of the more detailed descriptions. Parts of the text lead to additional information.‘To make parchment out of goatskins in Bolognese manner. Take goatskins (1) and stand them in water for a day and a night. Take them and wash them till the water runs clear (2). Take an entirely new bath and place therein old lime (calcem non recentem) and water mixing well together to for a thick cloudy liquor. Place the skins into this, folding them on the flesh side. Move them with a pole two or three times each day, leaving them for eight days (and twice as long in winter) (3).

Next you must withdraw the skins and unhair them (4). Pour off the contents of the bath and repeat the process using the same quantities, placing the skins in the lime liquor, and moving them once each day over eight days as before (5).

Then take them out and wash them well until the water runs quite clean (6). Place them in another bath with clean water and leave them for two days (7).

Then take them out, attach the cords and tie them to the circular frame (8). Dry, then shave them with a sharp knife, after which, leave for two days out of the sun…(9). Moisten with water and rub the flesh side with powdered pumice (10). After two days wet it again by sprinkling with a little water and fully clean the flesh side with pumice so as to make it quite wet again (11). Then tighten up the cords, equalise the tension so that the sheet will become permanent.

Once the sheets are dry, nothing further remains to be done (12).'

Schedula diversarium artium.

Theophilus Presbyter. Early twelfth century.

Written in Latin in Germany.

Britisch Museum MS. Harley 3915, fol. 148r.

R. Reed: Ancient Skins, Parchments and Leathers, Seminar Press, Londen en New York, 1972, p.133-134.

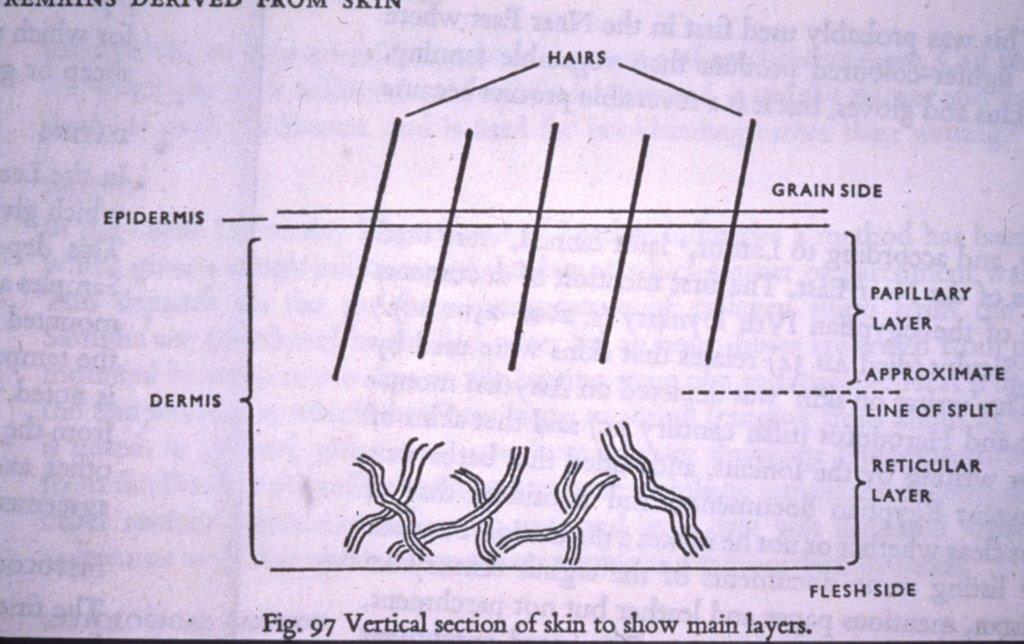

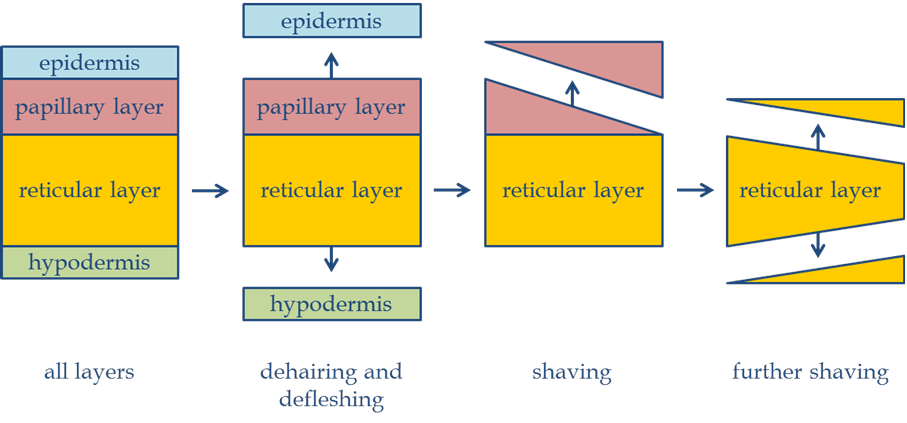

The process is summarised in diagram form (13).

1. ‘Take goatskins’

Not only goatskins but calfskins are perfectly suitable. In the Netherlands the two sorts have always been in use. In Italy and France sheepskin has been, and still is much in use. How fresher the skin how easier it is to clean, especially from blood. We notice how difficult it is to remove coagulated blood when handling a skin from an animal that has not been slaughtered or bled. The parchmentmaker can, however, make use of this effect, producing a veined parchment which can be very beautiful. This is not much used by restorers as the iron in the blood may eventually have an effect on the skin. The skin from an unborn calf, or one that is born dead, a small lamb or young goat provides the best material for parchment being supple, soft and yet quite strong. For this the Germans use the term 'Jungfernpergament'.

|

|

|

| sheep | goat | calf |

back up

2. 'and stand them in water for a day or a night. Take them and wash them until the water runs clear'

The skins are throughly soaked and swell up. The lime can then penetrate deeply into the skin. The salt that is rubbed into the skin whilst it is being flayed is washed out, as well as dirt and blood particles. A poorly treated skin must first have the fat and any remainig flesh removed. If this is not done then there will be ugly spots where the blood has soakes into the skin. Where too much flesh or fat is left on the skin then the lime cannot penetrate evenly. The intention is that at this stage, the swallon skin must have a regular open structure across the entire area.

back up

3. 'Take an entirely new bath and place therein old lime (calcem non recentem) and water mixing well together to form a thick cloudy liquor. Place the skins into this, folding them on the flesh side. Move them with a pole two or three times each day, leaving them for eight days(and twice as long in winter).'

The lime penetrates the skin and at first attacks the soft parts. This is the fat and the albumen in and around the hair follicles, loosening the hair. The follicle is the spot in the skin where the hair grows. The lime also works into the albumen-rich parts which exist between the fibres of the skin. Soluble chalk deposits are formed. According to other recipes where old lime is mentioned it is more then likely that this refers to lime already used for removing hair. Unknown before the middle ages, and for a long time after, this forms natrium sulphide, a cemical that speeds up the process of unhairing and having a deeper penetration. The fleshside must be turned outward so that the lime can penetrate more easily. It is only possible to smeer the wet and swollen fleshside of the skin with lime. It is folded double with the fleshside on the inside and laid in a closed vat. The skins will then still remain damp enough for the hair to be removed without the hair getting into contact with the lime as happens with a lime bath. This is a particulary good method for removing clean wool from sheepskin. The recipe specifically mentions 'mixing well' because the lime must work evenly over the entire skin.

back up

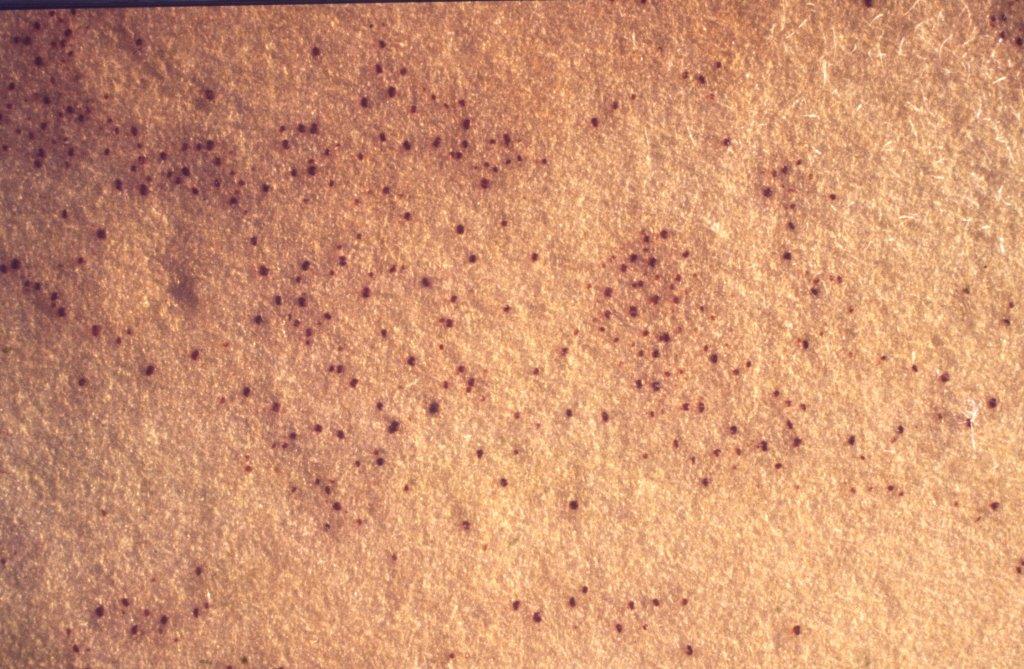

4. 'Next you must withdraw the skins and unhair them.'

|

||

| dehairing |

The skin is laid on a beam. This is a half round stem that stands at an angle to the ground. Using a blunt, concave knife the hair can be easely scraped from the skin which is laid over the wood and moved as necessary. It is important that as much as possible is removed including the sweat pores, hair roots, sebaceous glands and surrounding materials. If this is not properly carried out the skin can quickly deteriorate, or become hard and with too much fat, cause ugly flecks.

Using a sharp defleshing knife all the remaining fat and fat membranes (hypodermis) are removed. Finally the skin is thoroughly rinsed until the water remains clear.

|

||

| defleshing |

back up

5. 'Pour off the contents of the bath and repeat the process using the same quantities, placing the skins in the lime liquor, and moving them once each day over eight days as before.'

The skin, which is now laid with the hair side open, is ready to take new, fresh and stronger lime. The skill is in preparing the bath so that, depending on the skin sort and the temperature, as much as possible of the remaining substances can be freed from the skin, rather than the skin fibres.

back up

6. 'Then take them out…'

The skin is again laid across the beam and scraped clean on both sides.

back up

7. '…and wash them untill the water runs quite clean. Place them in another bath with clean water and leave them for two days.'

The cleaning process is continued. The skin is "reasonably" clean because not all the lime must be removed, as the parchment must retain an even white tint over the entire surface. Also a skin without lime cannot remain damp for long without the risk of deterioration.

back up

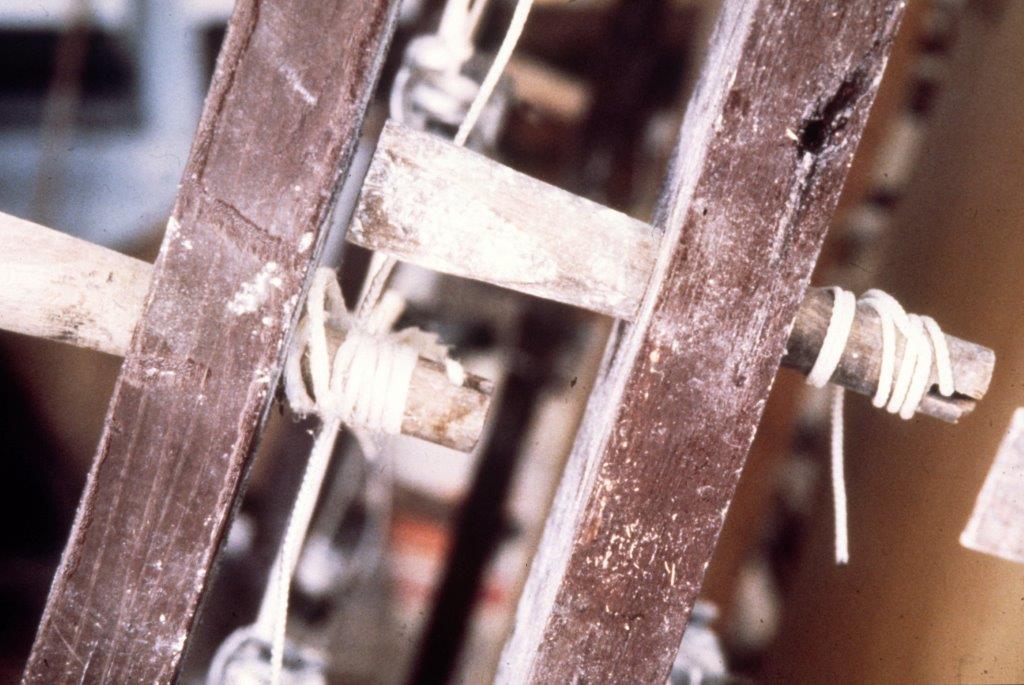

8. 'Then take them out, attach the cords and tie them to the circular frame.'

The cords were tied to the skin and kept streched with stones, balls of parchment, sticks or with string, today rustfree metal clamps are also used.

|

| pegs and cords |

|

| drum |

back up

9. 'Dry, then shave them with a sharp knife, after which, leave for two days out of the sun…'

|

| shaving |

|

| half moon knife |

back up

10. '…moisten with water and rub the flesh side with powdered pumice.'

Indeed it is the flesh side that requires so much attention. This side must be continually scraped until an open, velvet like structure is obtained.

|

||

| pumicing |

back up

11. 'After two days wet it again by sprinkling with a little water and fully clean the flesh side with pumice so as to make it quite wet again.'

I have experienced this aspect of being very important indeed. By making the flesh side slightly damp over small areas at a time, only the remaining fibres absorb the moisture. These then come loose from the underlayer which remains dry. There is a difference in tension so that the wet fibres are easy removable with pumice and chalk. The flesh side now gains its velvety surface.To make the surface smooth again it is only necessary to wipe it with a damp cloth, making the fibres lie flat.

back up

12. 'Then tighten up the cords, equalise the tension so that the sheet will become permanent. Once the sheets are dry, nothing further remains to be done.'

Finally the half moon knife, sharpened and then given a burr on one side, is used as a scraper to remove a thin horny layer from the surface of the hairside. When this is carried out both sides have the same characteristics and with the parchment being thinner can be used for restoration purposes, a quality also much in demand with calligraphers.

|

||

| presenting the parchment |

back up

13. Process diagram

|

| Process diagram |